In the early 1900s, the sainete was a short theatrical form in one or two acts, which in Buenos Aires became very popular as the demand for inexpensive entertainment grew with the city’s populace. Alberto Vaccarezza was one of the form’s most successful writers…

Viewing entries in

1920s

One of my favorite tunes in the songbook is the beautifully written tango “Una pena,” familiar to most dancers in the delicate D’Agostino-Vargas rendition…

The tango “Dandy” came out of a successful trio that toured Europe in the 1920s, with Lucio Demare on piano, accompanying the two singers Agustín Irusta and Roberto Fugazot.

Playwright José González Castillo wrote his 1923 tango “Sobre el pucho” for a contest sponsored by the “Tango” cigarette company, the first competition of its kind to require tangos with lyrics.

Manuel Romero wrote a one-act titled El bailarín del cabaret in 1922 for a comic actor named César Ratti, who was the head of the Apolo theater in Buenos Aires. The ephemeral show did prove to hold one major attraction, but it was destined to showcase a different talent: the gifted fair-haired singer Ignacio Corsini, who performed the tango “Patotero sentimental” onstage as part of the action.

Carlos Lenzi’s now famous lyrics for the 1925 tango “A media luz” rode a catchy tune to a hit status, and its staying power has proven the song a classic through the decades.

The tango lyricist credited as Luis Mario, or sometimes as Mario Castro, was in reality María Luisa Carnelli—one of the few women who wrote lyrics for tangos during the Golden Age.

The 1926 tango “Tiempos viejos” is a classic song for a few different reasons, whose intertwining tells us some important things about the tango’s backstory…

The lyric of “Muchacho” by Celedonio Flores partakes of that most ancient of poetic modes, the put-down. Here we see the poet turning his satirical wits against the figure who is usually on the periphery in his other songs—the stuck-up son of privilege.

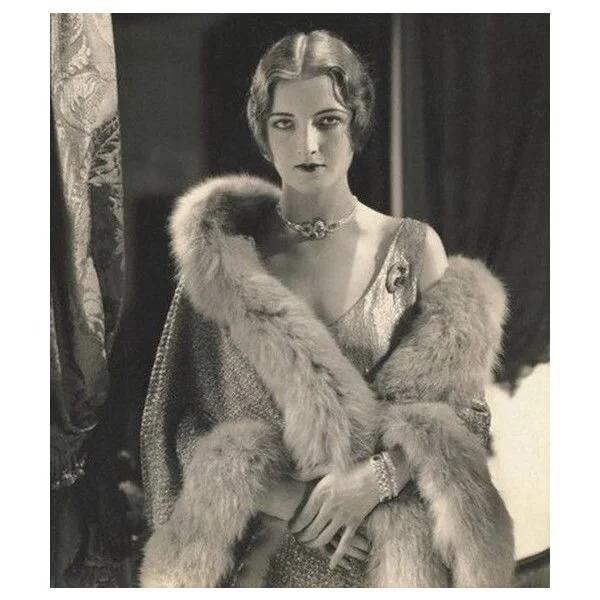

The young woman depicted here is one of many French working girls, usually shop attendants or seamstresses, known as grisettes for the gray flower-print dresses they originally wore in the 1830s.

Loved by many dancers for its fateful melody and its atmospheric story, the tango “Duelo criollo” departs from the cabaret cityscape of the 1920s to depict a scene that then obsessed the urban mind: the daring knife fights of the roughnecks in the hard scrabble of the outskirts.

When it comes to the history of popular music, we can trace how authors played with various trends and crosscurrents of the times. And at a certain point, we can observe that the biggest influence on the tango was in fact the tango itself. The tango “Zorro gris” provides an interesting case in point.

We usually think of that iconic tune “La cumparsita” as the most famous tango of them all, holding as it does the honor spot as the last song of the night played for dancing in modern milongas. But perhaps the only tango more widely recorded and more widely known in its heyday is ironically the one which, as a rule, is never played at milongas now—the 1927 song “Adios, muchachos.”

With the 1924 hit “Suerte loca,” Francisco García Jiménez showed how well a tango could work with clever extended metaphor, and elevated the genre into cerebral territory that only witty poetry occupied at the time.

Considered one the early masterpieces among tango lyrics, the lunfardo-heavy “Mano a mano” is perhaps the most famous work of Celedonio Flores—and a song with its own controversies too.

If tango lyrics collectively comprise a kind of epic soap opera, then that poem’s opening chapter centers on the 1920 tango “Milonguita.”

Lyricist Francisco García Jiménez was an early innovator in tango lyrics, elevating their style with his refined technique, poignant sensibility, and greater range of lyrical devices.

“Caminito” is one of the tango’s all-time classics, and dates from the earlier period of the genre’s songbook.